Why Blade Runner is a Masterpiece

Blade Runner. Image courtesy of Warner Bros.

Blade Runner was one of those movies that just left me in awe. I was a teenager when I first watched it and it’s one of the films that made me truly love cinema. There is just so much going on in this film, from the backstory of its development and release, to its iconic production design, its heady philosophical themes about the Nature of Man and the sublime synthiness of its score. Often copied but never replicated, Blade Runner is a true masterpiece of cinema.

But what makes it a masterpiece? The first is that, like God’s love, it takes many forms. There is the Blade Runner that was released into theaters in 1982, which the studio forced Ridley Scott to change by adding a notoriously terrible Harrison Ford voice over and switching the ending entirely so that the main characters drove away into the mountains in bliss (using b-roll from The Shining, which if we take this shit literally means they are actually driving toward the Overlook Hotel).

There is also a remastered 2007 edition, with some added special effects. The best edition, I think, is the 1992 directors cut which is the closest thing to Ridley Scott’s original, unaltered vision for the film. This kind of behind the scenes drama always gives films a little extra emphasis, because it means people were willing to fight to see the real thing. If Zack Snyder announced that the studio made him change the ending of the Owls of Ga’Hoole and he had the directors cut stashed somewhere, I’m quite sure nobody would fight for its release.

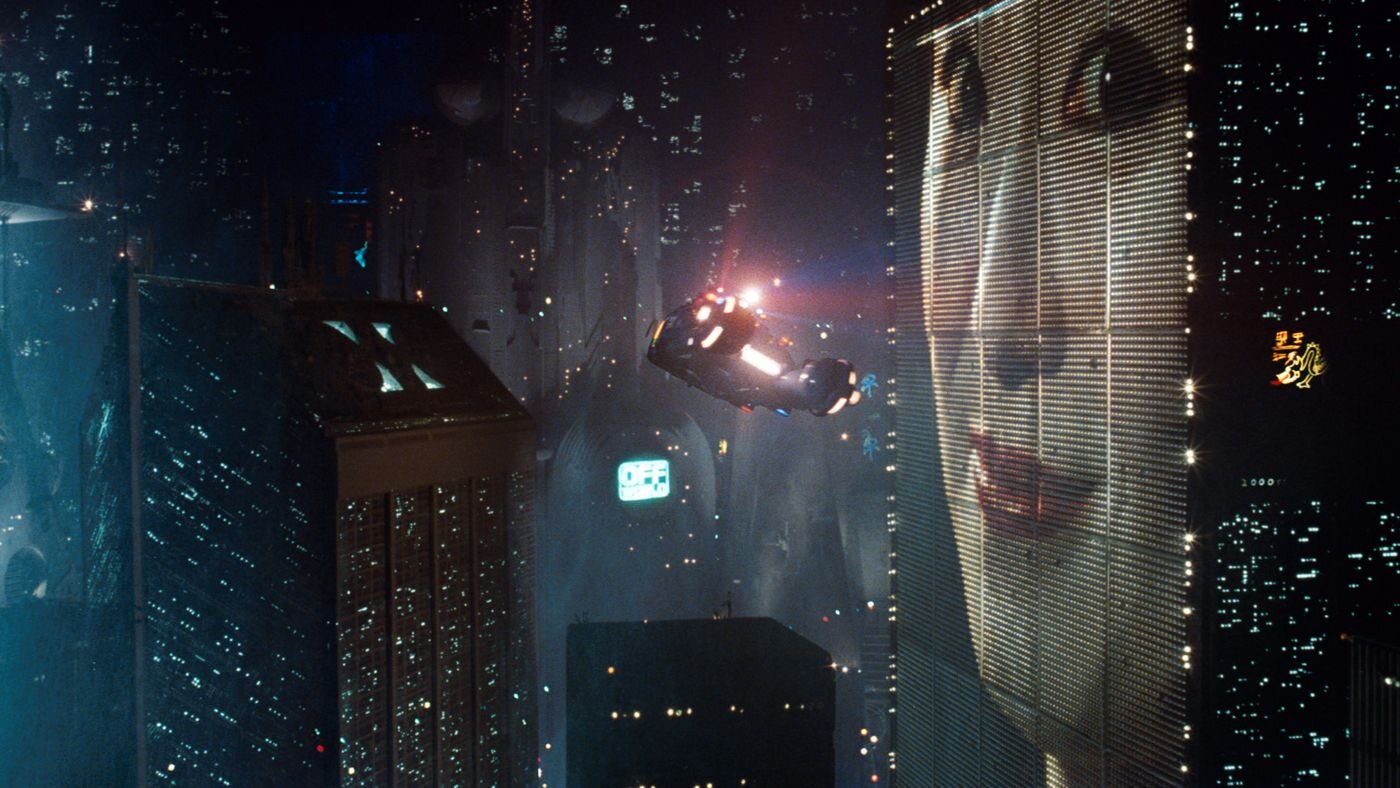

It goes without saying that the production design on Blade Runner is iconic and almost indescribably influential. The early 1980s was the peak of the neo-noir wave, and Blade Runner seamlessly fused noir elements with sci-fi imagery to create a classic dystopian vision of the future. I talked about this in my review of Alien. The real strength of that film is the mood and the atmosphere it creates through immaculate production design and visual world building. Blade Runner does the same thing, layer after layer of complex, rich detail that sucks you fully into its world and makes you feel a sense of both awe and unease.

Blade Runner / Courtesy Warner Bros

It’s got the rain-slicked, oily feel of a real techno-future metropolis, where clones might indeed be hunted in back alleys while the Masters of the Universe in their floating castles experiment with the essence of life. All of this is complemented by a pitch-perfect synth-laden Vangelis score that somehow fits the film’s visual language and thematic depth in a way that is rather uncanny. The world building, the visual imagery, the production design of this film - it is all impeccable.

But what ultimately elevates Blade Runner to a masterpiece is that it takes all of this visual magic and uses it in service of a complicated narrative that asks big questions, like what is the meaning of life? Ridley Scott would return to these Big Questions with Prometheus and Alien: Covenant, and people screamed because what they wanted to see was an alien suck the spine out of a headless corpse. You need to read the room, I guess.

Blade Runner did dare to ask these questions, and it answered them in the oblique, shimmering way of all high art - by having Rutger Hauer sit down in a rain storm clutching a dove and making perhaps one of the most profound and beautiful soliloquies in film history.

"I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.”

What makes this moment so powerful? It’s because the full force of the film with all of its production design, its heady themes, its score that stabs at the soul, its wounded characters and dystopian atmosphere - it’s all building to this moment, where a machine becomes a man by quoting poetry into the rain as he dies.

The technical aspects of the film are amazing. The themes are deep. The acting is excellent. And the alchemy of cinema is such that all these things reach their full and natural expression in that moment and it became an instant classic in film history. I could go on and on about Blade Runner, and the reasons why it is a masterpiece. But I will just close by pointing to its sequel, Blade Runner: 2049, to illustrate just how profound and powerful the original really was.

Blade Runner: 2049 has the look and feel of a masterpiece. It borrows the visual language of the original and uses a more muscular budget and modern effects to expand the future that was imagined in 1982. It looks beautiful, moving languidly through various set pieces, like a Las Vegas shrouded in radioactive orange haze. But it only looks like a masterpiece. It doesn’t, at least in my mind, have anything very profound to say at all by the time the credits roll, and nothing even close to the power and the glory of that moment in time created by Rutger Hauer, Ridley Scott a little rain and a pigeon.